For neighborhoods, a question of ‘teeth’ versus autonomy

By DYLAN THOMAS : The Journal : MAY 30, 2017

A Charter Commission taskforce is exploring the possibility of more clearly defining the role of neighborhood organizations in ordinance or even the charter itself, a change that could fundamentally shift the relationship between the city and the 70 independent non-profit organizations that represent 84 Minneapolis neighborhoods.

The taskforce met twice this spring to study the legal framework supporting Minneapolis neighborhood organizations and compare what we do here to other big cities across the country — including New York City, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., three cities that, unlike Minneapolis, recognize neighborhoods in their charters. They discussed the pros and cons of defining the role of neighborhood organizations in statute: Neighborhoods could gain influence on matters of development and city planning, but they might sacrifice their autonomy to get it.

For now, that’s just conjecture. DJ Heinle, who organized the taskforce with fellow Charter Commission member Jana Metge, said the group was still in a “fact-finding” phase and may not ever produce a recommendation. They plan to invite City Attorney Susan Segal to a meeting for advice on any “pitfalls” before proposing a change, Heinle said.

While Heinle said he liked the idea of neighborhoods “having a little more teeth,” others think Minneapolis has ceded too much power to neighborhood organizations already. Corcoran resident Peter Bajurny is among those calling for the organizations to be reined-in.

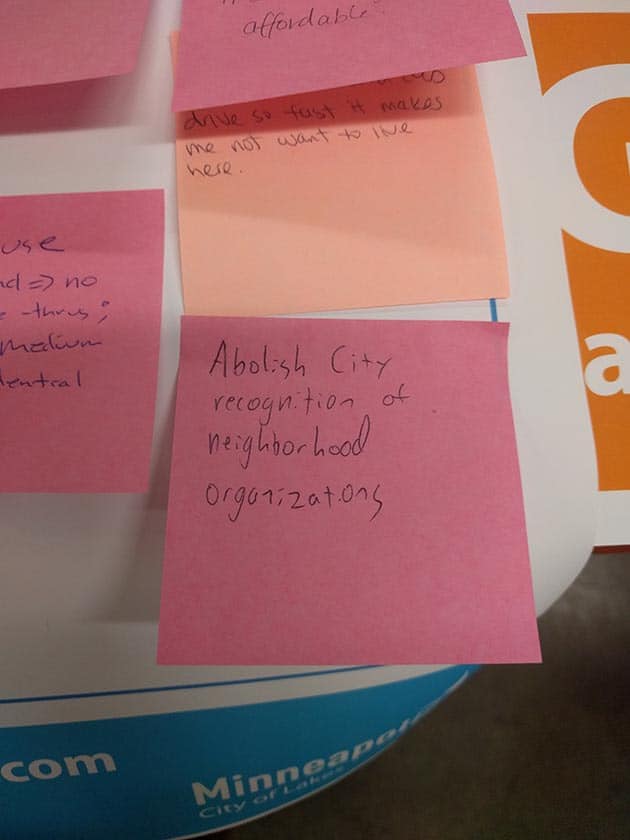

Bajurny, who works in information technology at the University of Minnesota and contributes to the website streets.mn, caused a political tempest this winter with a comment he submitted on Minneapolis 2040, the city’s next comprehensive plan update. His suggestion to “abolish city recognition of neighborhood organizations” became a bullet point in a staff report on community engagement, prompting 17 neighborhood organizations to pass a resolution demanding its removal.

“It’s kind of humbling to have caused this much uproar with a simple Post-it Note,” Bajurny said in an interview in May.

The comment stayed in the report, but the City Council responded to the outcry by passing a resolution of its own, one that recognized the “core and vital service neighborhood organizations provide to the City of Minneapolis.”

Heinle said the episode inspired the formation of the Charter Commission taskforce.

Defining neighborhood power

Along with Seattle and Portland, Minneapolis has one of the oldest and best-established neighborhood programs in the country. Between the still-active Neighborhood Revitalization Program and its successor, the Community Participation Program, Minneapolis pumps $6 million–$7 million into neighborhood organizations each year — on a per capita basis, perhaps the highest level of support in the country, said David Rubedor, director of Neighborhood and Community Relations.

While Minneapolis ordinance requires neighborhood organizations to be informed of some pending zoning, permitting and licensing decisions, as well as any changes to City Council Ward boundaries, the city statutes don’t give the groups the same clearly defined powers found on other cities’ books.

Jeff Schneider of the Minneapolis City Coordinator’s Office, who has been researching neighborhood programs and presented preliminary findings to the taskforce in May, said Washington D.C. ordinance requires government entities to give “great weight” to the recommendations of its neighborhood commissions, language that has withstood challenges in court. The commissions have the power to call public hearings, and city departments are required to answer to the commissions for their decisions.

In L.A., ordinance gives its neighborhood councils a role in setting budget priorities and monitoring the delivery of city services. L.A. even requires city department heads to meet regularly with the councils, Schneider said.

“I love this L.A. ordinance,” Metge remarked as the Charter Commission taskforce reviewed those statutes in May.

But Rubedor urged caution in that same meeting, noting that the “beauty” and the “challenge” of Minneapolis’ system is that those 70 independent nonprofits “can do what they want,” independent of the city.

“As they get closer to having stronger recognition by the city, then they start running into issues of whether, legally, they are an extension of the city, which then means that there’s a potential loss of autonomy,” Rubedor added later in an interview. He said a shift in the relationship could also raise liability concerns if neighborhood organizations had to abide by the rules and regulations that govern city operations.

Both Heinle and Metge bring to the Charter Commission their experiences with neighborhood work. Heinle served on the North Loop Neighborhood Association board for about eight years and Metge is both the coordinator for Citizens for a Loring Park Community and a representative to her own neighborhood’s board, Midtown Phillips Neighborhood Association.

Metge declined to comment for this story, but Heinle said he, too, was taken with the description of L.A.’s neighborhood system. While Heinle’s experience as a North Loop board member was positive, he said other neighborhoods struggled to engage with city departments or even their own City Council member.

“I don’t think it always goes as well with some of the other neighborhood organizations,” he said.

A voice on development

It was concern about the city’s rental housing crunch that prompted Bajurny to show up for a Minneapolis 2040 community input session. He said he wanted the next comprehensive plan to be a “pro-growth document,” one that welcomed and helped to accommodate Minneapolis’ growing population through the zoning code.

“I think some of our most affordable neighborhoods are ones where there are small apartment buildings or duplexes or triplexes in the neighborhood interiors,” he said. “I think the comprehensive plan should encourage that, or at the very least not be an impediment against it.”

In Bajurny’s view, zoning isn’t the only impediment to adding more rental housing. While they issue opinions on a strictly advisory basis, neighborhood organizations play a key role in many development projects, often meeting repeatedly with developers to offer their feedback.

“A lot of Council members will treat the views of neighborhood organizations as very important,” Bajurny said, adding that resolutions issued by neighborhood organizations are often interpreted as “what the neighborhood wants.”

But as Bajurny noted and the city’s own demographic surveys of neighborhood organizations have demonstrated, neighborhood boards don’t exactly mirror their communities. They tend to be whiter and better educated than the neighborhoods they represent, and the elected boards are disproportionately made up of homeowners rather than renters.

“They’re 25 years into their 30-year mortgage or they’ve already paid it off, and they don’t need new housing. They’ve got their housing,” Bajurny said. “Their voice I don’t think is the most important one at the table when it comes to new development and welcoming people to our city.”

Bajurny said his concern about organizations’ influence extends to others areas where neighborhoods regularly provide input, include street design and bicycle and pedestrian projects.

Engagement challenges

Bajurny, too, has volunteered with his neighborhood organization, serving on its Land Use and Housing Committee and representing Corcoran on the Midtown Greenway Coalition board. He said his experience has been positive — partly because it’s a “well-run organization,” but also because he has the time and ability to participate.

“I’ve had a positive experience because I am a middle-class, white male who has a nine-to-five job,” he said, noting that it’s no problem to attend evening board meetings or even cut out of work early to get to an event. But he said that’s not the case for everyone, particularly younger and lower-income residents, who may not have the time for — or interest in — attending neighborhood meetings.

“There’s all these systemic barriers when the whole premise revolves around getting everyone in a room together for a couple of hours at 6 o’clock at night,” he said.

Heinle agreed that it’s particularly difficult for the organizations to connect with renters.

“We really struggled with that, I think, when I served on the North Loop (board),” he said.

But Heinle also said homeowners tend to be “more rooted in the neighborhood,” and if neighborhood organizations amplify their voices enough to be heard by city leaders, “that could be a positive, too.”

Rubedor, who flew to Phoenix in late May to speak on Minneapolis’ neighborhood system at the Summit on Government Performance and Innovation, said both Seattle and Portland are, like Minneapolis, currently grappling with how to better engage diverse populations at the neighborhood level. The dawning recognition that not everyone connects to a city through the neighborhood shows “cities are getting a little wiser,” Schneider said.