Everything is awesome! Southwest LRT officials make the case that the project isn’t the smoldering tire fire so many assume

The people responsible for keeping Southwest Light Rail Transit moving forward think the $1.858 billion project is getting a bad rap.

And after weathering yet another stretch of seeming setbacks and new hurdles, the Metropolitan Council and elected officials from governments along the route are trying to change the narrative of Southwest LRT as a project in peril.

Those officials point out that within the last month, the project has won a longstanding lawsuit by opponents; produced another environmental review (triggered in part by new demands from the BNSF railroad); resolved a conflict with another railroad over demands for sharing right of way; and witnessed the passage of a federal transit budget that set a record for its generosity toward light rail funding.

“Earlier this year, the president’s budget had proposed to eliminate the (Capital Investment Grants) program entirely and Congress acted to not only fund the program but to give it an all-time-high appropriation, a record high,” said Met Council Chair Alene Tchourumoff at a Wednesday meeting of state and local government officials who help direct SWLRT.

In fact, things are going so well that Hennepin County Commissioner Peter McLaughlin said the backers of the project need to brag a bit more. “One of our jobs is to be upbeat and tell the story,” McLaughlin said.

He also offered a bit of a history lesson. While SWLRT has suffered numerous setbacks and continues to have critics, he said, there were similar headaches with the region’s first light rail project — originally known as the Hiawatha Line — between downtown Minneapolis and the airport.

“Hiawatha was called the train to nowhere until it opened up,” he said. “Now there’s a hell of a lot of people going to nowhere everyday.”

Light rail doomed under Trump? Not so much.

Next week, a delegation that includes members of the Met Council, local government officials, and Twin Cities business community will make a pilgrimage to Washington, D.C., to make the case to the federal government that the project is back on track.

“We still need the appropriation from the FTA, and I think it is important for us to demonstrate that we’re ready,” Tchourumoff said. “And with the number of milestones we have hit just here in the last couple of weeks we need to be able to tick off those milestones.”

Trump’s budget proposal — or, rather, his lack of a budget for new rail and streetcar lines — has driven much of the media coverage, thanks in no small part to a narrative pushed by interest groups. With Trump in the White House, the story went, light rail was doomed.

But as with Trump’s first supplemental budget and first annual budget, Congress ignored the administration and continued a deal dating back to the Reagan administration to provide certain percentages of transportation money to transit.

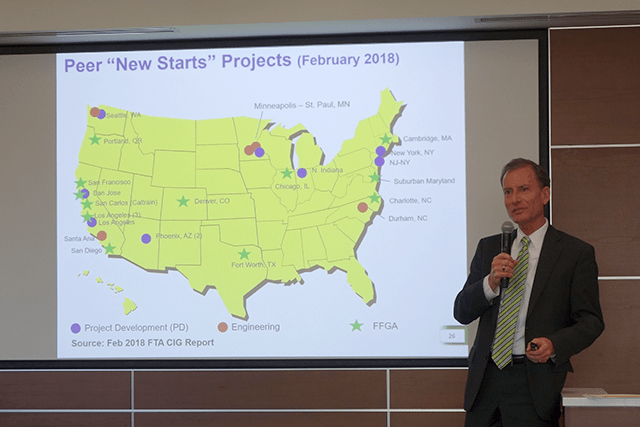

The federal budget that passed with bipartisan votes and was signed by Trump earlier this month follows that same pattern. Included are buckets of money for what are called “New Starts,” such as the SWLRT to Eden Prairie, the Bottineau Line to Brooklyn Park and the Gold Line bus rapid transit line between St. Paul and Woodbury as well as “Small Starts” including the Orange Line BRT between Lakeville and Minneapolis. All were cited in a February FTA report on projects that are in line for federal funding, though the document followed the White House stance of requesting no money for new projects.

Both New Starts and Small Starts not only received more money than was expected, the budget also contained specific language directing the FTA to spend the money, language Tchourumoff said was intended to make it difficult for a Trump FTA to not reach agreements with local transit agencies and not distribute the money.

While the bulk of the New Starts money is to go to projects already under construction, $401 million is set aside for the five projects in line for full-funding grant agreements in the next year. Two of those are SWLRT and the Bottineau Line, with the others being projects in Santa Ana, California; Seattle; and Durham, North Carolina.

If it’s Tuesday, the Minnesota Legislature is trying to kill Southwest LRT

The good news is tempered by a series of bills and proposals from Republicans in the Legislature to block construction of SWLRT.

Since the 2017 session, when similar bills were eventually blocked by Gov. Mark Dayton, the shares of nonfederal funding for the project have changed. The state is no longer being asked to cover part of the construction (though it will be asked to maintain its 50 percent share of operating funds, similar to the share it carries for the existing Blue Line and Green Line).

Today, through an increased county sales tax , Hennepin County is now the only nonfederal funder of the project.

That, however, hasn’t ended efforts at the Capitol to kill the project. One bill would allow Plymouth and Maple Grove to request half of the increased sales tax collected there and use it for highway projects. That would reduce the funds available for projects like SWLRT and Bottineau.

Another bill would ban colocation of freight and passenger rail, something that is being planned for both light rail projects.

“Even though Southwest is no longer looking for state funding and doesn’t really need any state support … we are still continuing to see attempts to stop the project,” Tchourumoff said.

A series of unfortunate events

SWLRT backers are trying to be upbeat not because they deny having had a rough period but because they think they’ve survived it. Project managers had hoped to be starting some construction work in the fall of 2017. But then a series of setbacks arose that have set the often-delayed project back by a year.

The first setback came when Metro Transit received the initial bids on the largest single contract: the civil construction work that includes track, stations, parking lots, a parking ramp, retaining walls, bridges, pedestrian tunnels and two light rail tunnels. All four bids were rejected because they were too high, and all bidders were disqualified because they didn’t follow state bidding rules when they all included subcontractors who had helped design the project. New bids for the civil construction work are now expected to be opened in May.

If the bids come in close to what the project staff thinks is reasonable, a winner might be awarded in August. And even though the Met Council isn’t anticipating receiving a full-funding grant agreement from the FTA until 2019, federal rules allow work to begin before that — if the FTA agrees. So while full construction wouldn’t start until spring of 2019, some work could be done this fall, with passengers possibly riding the 14.5 mile extension in 2023.

There were also onerous demands by the BNSF railroad to build a one-mile collision wall to separate passenger rail from freight rail. Not only would the design of such a wall take time, but Southwest LRT project staffers were ordered by the FTA to conduct further environmental review. That process should also be completed in May.

The Met Council also seems to have headed off demands by the Twin Cities and Western Railroad, requests the project staff considered excessive. TC & W doesn’t own the tracks through the Kenilworth Corridor or the trackage south of it known as the Bass Lake Spur. That right of way is to be owned by the Met Council. But TC & W had some leverage because it served as the common carrier under federal law, a designation that makes it responsible for assuring that the tracks would be available to any shipper needing to use them.

When a deal couldn’t be struck, the Met Council asked Hennepin County and the Hennepin County Regional Rail Authority to take over common carrier responsibilities. (The Met Council didn’t take on the responsibility itself because it didn’t think it had legal authority under state law to do so.)

SWLRT Project Director Jim Alexander said the change in common carrier designation was “inside baseball” and didn’t change the construction process at all. But being pressured to change the arrangement led to some frustration by Hennepin County Commissioner Mike Opat, who referred to it as “bureaucratic gymnastics.”

“We take on these hugely complicated things and then we discuss them for five minutes like it’s no big deal,” Opat said at a commission meeting in early March. “It’s not a five-minute proposition.”

Of the SLWRT project in general, Opat said: “There’s a steady drip, drip, drip of accommodations we need to make to keep this going and they’re all time intensive and they’re all staff intensive.”

On Wednesday, Hennepin County Board Chair Jan Callison acknowledged the lengthy process, but said Southwest LRT would be worth it in the end. “These are hugely complicated projects and this one is more complicated that we wish it were sometimes,” she said.

But about that price tag …

The official budget for the 15-station extension of the existing Green Line is $1.858 billion. If a full-funding grant agreement is reached, the federal government will cover half of that: $929 million. But that budget was set in 2016. And because it was the budget amount when the FTA authorized the Met Council to enter the final phase of engineering, it is the maximum the feds will pay.

So any increases caused by unforeseen costs (hello, collision walls) or inflation — a figure Metro Transit’s Mark Fuhrmann, who oversees the Southwest LRT project, estimates to be $1 million a week — will have to be resolved locally. And the only source of additional funding is Hennepin County or the Hennepin County Regional Rail Authority.

“Those are questions that we can work through with more definity once we open those civil bids,” Fuhrmann said. “It may be a combination of doing some budget adjustments, it may be looking at some additional funding slash contingency. But we’re not able to quantify any of that until we see where we sit with the bid opening.”