Met Council’s agreements with railroads raise concerns in Minneapolis

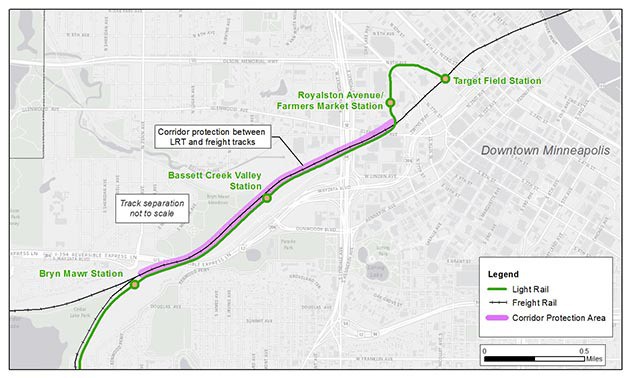

The Metropolitan Council agreed with BNSF to add a 10-foot-high, 3-foot-thick wall along a roughly mile-long stretch of the future Southwest Light Rail Transit corridor. Image courtesy Met Council

By DYLAN THOMAS : The Journal : AUGUST 18, 2017

Minneapolis officials expressed concern at the Metropolitan Council’s plans, announced in mid-August, to add 10-foot-high, 3-foot-wide crash wall along a roughly mile-long section of the Southwest Light Rail Transit corridor.

The wall was a late addition to the nearly $1.9-billion SWLRT project, which will extend the METRO Green Line 14.5 miles to Eden Prairie. From the perspective of Minneapolis officials, the wall was just one of the surprises contained in a series of agreements Met Council officials negotiated with two freight rail operators, BNSF and Twin Cities and Western, both of which will share a portion of the SWLRT corridor through Minneapolis.

Met Council members unanimously approved the agreements Aug. 16.

City Council Member Kevin Reich criticized a “lack of transparency” in the negotiations around the wall, intended to serve as a barrier between light rail and freight trains, which he said city officials first learned about less than a week before the vote. Reich, who chairs the council’s Transportation Committee, also raised questions about plans to shift the Cedar Lake Trail, a popular bicycle and pedestrian path that runs parallel to the future light rail line, as well as the Met Council’s commitment to accept liability for any incidents involving both freight and light rail trains in a shared corridor owned by BNSF.

SWLRT Project Director Jim Alexander said “corridor protection” — the wall — was included in light rail plans, but it didn’t previously extend the full length of the Wayzata Subdivision, the name for a 1.4-mile stretch of BNSF-owned railroad corridor stretching from just south of Interstate 394 to the North Loop. The agreement with BNSF also calls for a new “tail track” for storing Northstar Commuter Rail vehicles when they are not in use, which Alexander described as yet another “new piece” in the project.

BNSF currently has a single track in the Wayzata Subdivision, but Alexander said the railroad’s position in negotiations was that it needed to preserve the option to add a second track in the future. In his presentation to the Met Council’s Transportation Committee, he referred to it as the railroad’s “150 year plan.”

Alexander said the project team would be able to shift the Cedar Lake Trail to the south and maintain its current width, although it would close during light rail construction. A public conversation on the design of the wall could begin as soon as September, he added.

In an Aug. 14 letter to Metro Transit General Manager Brian Lamb, Minneapolis Director of Public Works Robin Hutcheson wrote that city staff had “consistently maintained the position that barrier walls would be a detriment to the project and to the community,” adding that the city expected a “robust forum” to discuss the wall’s design and air community concerns. Hutcheson also noted the new components of the project could affect city assets, including the Bassett Creek Tunnel, which carries the creek to the Mississippi River beneath downtown. The tail track will be built on top of it, Alexander said.

Rep. Frank Hornstein and Sen. Scott Dibble, who both represent the portion of Minneapolis that includes the future SWLRT corridor, questioned several provisions of the shared-use agreement with BNSF that anticipate the possibility that the co-location of freight and light rail in one shared corridor could be challenged by future laws. Met Council agreed to either pay for modifications to the corridor or challenge those laws in court, and if either tactic fails, to suspend SWLRT operations.

While Alexander described the scenario as very unlikely, Hornstein noted in an interview that one possible outcome of the shared-use agreement would be Met Council suing the City of Minneapolis or some other local unit of government on behalf of BNSF. Hornstein said it appeared “Met Council basically bended to all the railroad’s interests here.”

“There’s no excuse, just because you’re negotiating with the private sector on something, that you have to freeze out key stakeholders,” he added.

Asked to respond to concerns about the negotiations, Alexander said those talks couldn’t even begin until the Federal Transit Administration issued its record of decision on the project last summer, a key step that marked the end of the environmental review phase for SWLRT. The wall and the new tail track came up very late in those conversations, Alexander said, adding that they remained privileged until he presented the details to the Met Council.

“We don’t have a lot of leeway to talk to outside parties about the nature or the content of the discussions,” he said. “That’s one of the challenges here.”

The construction agreement with TC&W includes up to $4.2 million to reimburse the railroad for costs incurred during construction and another $11.9 million to remove and replace rails in the area known as the Bass Lake Spur, located in St. Louis Park, to make way for SWLRT.

A purchase and sales agreement with BNSF includes up to $10 million in project funds to acquire property and permanent easements from the railroad along the Minneapolis portion of the SWLRT corridor. In a separate construction agreement with BNSF, Met Council agreed to cover pre-construction planning costs, estimated at about $1 million, plus another $4 million for project construction.

In its shared-use agreement with BNSF, Met Council commits to taking out a $295-million railroad liability policy to cover insurance claims related to incidents involving both freight and light rail. Alexander said the council has a similar policy for Northstar, which also operates on BNSF right-of-way.

With the agreements secured, Alexander said Met Council plans to submit its application in September for the Federal Transit Administration grant expected to cover half of project costs.

The Met Council in August also received four bids for SWLRT construction, ranging from about $797 million to almost $1.1 billion.