Loop Back: The North Loop’s Colorful History (Overview)

From the late 1800s to the 1930s, the North Loop was the center of a wholesaling and manufacturing boom that turned Minneapolis into one of the key distribution centers in the U.S.

Delivery wagons on 1st Street North. (MN Historical Society)

With its modern rail system expanding, the city was in a prime location to do big business with settlers, making their way across the prairies.

1920s aerial view (Hennepin County Library)

“As immigrants were settling in northwestern Minnesota, as the Dakota territories were opening for settlement, there was a huge demand for agricultural implements, all the plows that broke the prairie soil,” said historian Rolf Anderson.

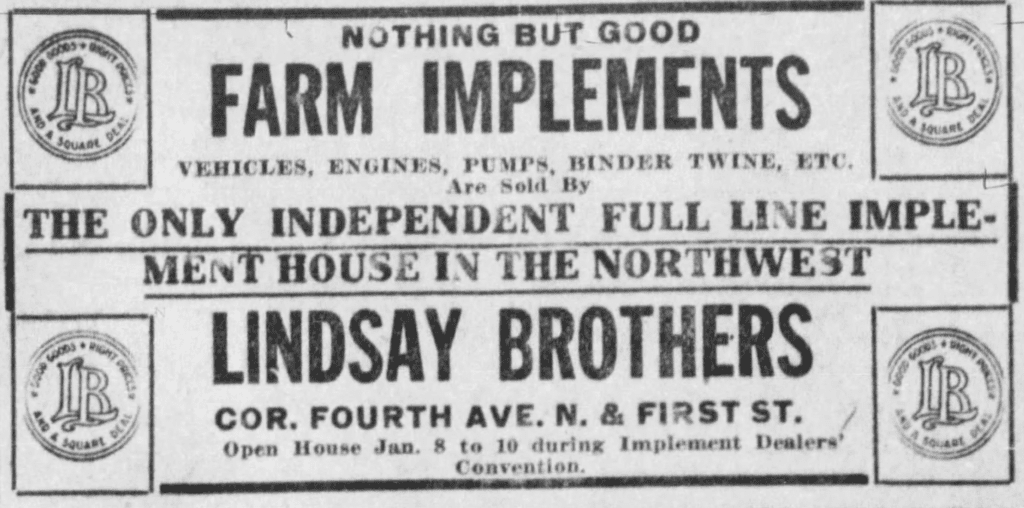

Lindsay Brothers on 1st Street North (MN Historical Society)

The Lindsay Brothers from Wisconsin built a warehouse along 1st Street in 1895, shipping out buggies, harnesses, wagons and “nothing but good farm implements” according to their ads.

1913 newspaper ad

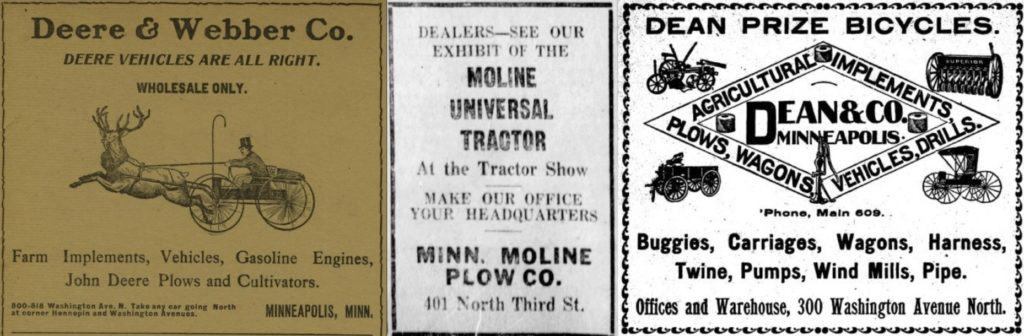

“There were many national firms that opened branches here in the Twin Cities to serve this area that was being settled,” said Anderson. “International Harvester for example. There was the Moline, Milburn and Stoddard Company, John Deere Company from Moline, Illinois.

“There was a point just after the turn of the 20th century where Minneapolis and this district became the largest distribution point in the world for agricultural implements, so the statistics are really quite remarkable,” said Anderson.

In fact, by 1915, what was happening in the Warehouse District was already generating more revenue than the city’s famous flour and grain mills. Wholesaling and warehousing became a billion dollar industry here in 1919. And it went beyond farm implements.

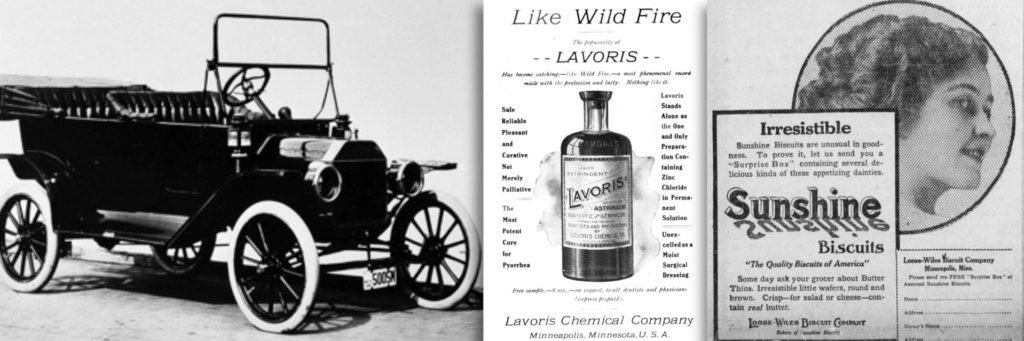

Manufacturers moved in to the rail yards too, producing and shipping everything from Model T Fords to Lavoris mouthwash and Sunshine Biscuits.

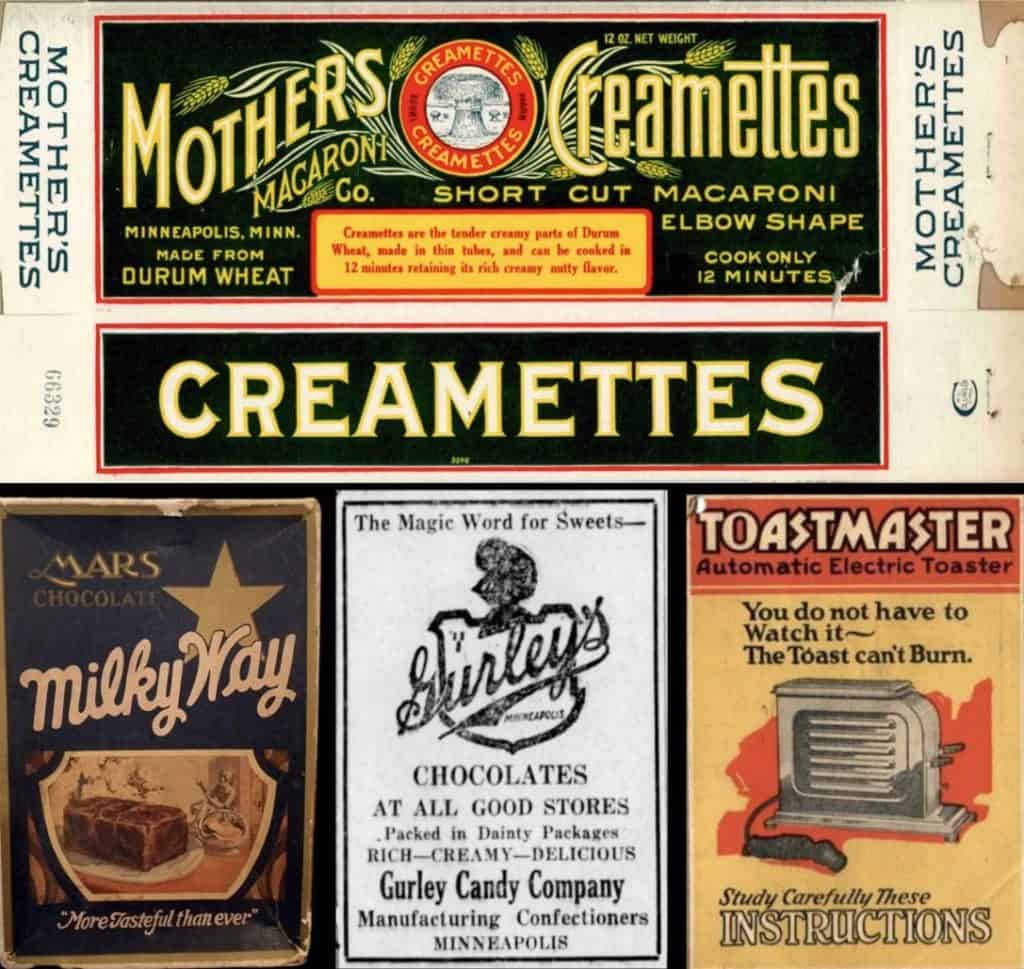

Creamette, with its quicker-cooking pasta, got its start in the North Loop. The Milky Way candy bar was born here in 1923 when Frank Mars and his son, Forrest, came up with an idea to create a candy bar that tasted like a malted milk shake. And the world’s first pop-up toaster was manufactured here in the North Loop by the Waters-Genter Company.

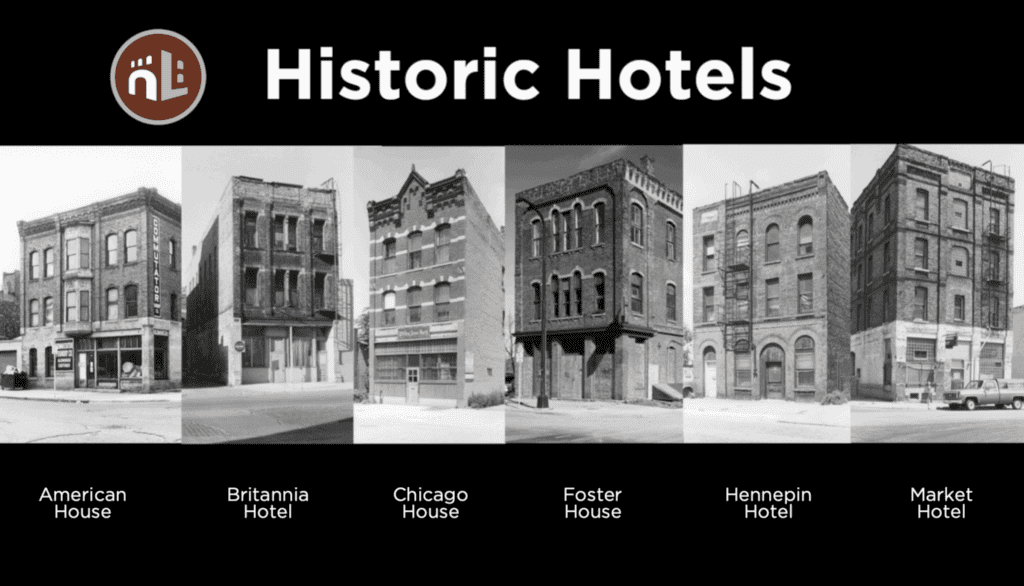

Five buildings still standing on First Street used to be hotels, including the Foster House (now an office building at 1st and 1st), Market Hotel (currently home to Kado No Mise restaurant), Hennepin Hotel, Chicago House and American House (later the Commutator Foundry and in 2025 incorporated into the West Hotel project).

“There were often livery stables and so forth because in the early years, of course, everyone was dependent upon horse-drawn traffic,” said Anderson. “In the early days, the streetcars were pulled by horses. The Colonial Warehouse building was owned by the Minneapolis Street Railway Company which, in fact, was the streetcar system.”

Photo courtesy: Hennepin Co. Library

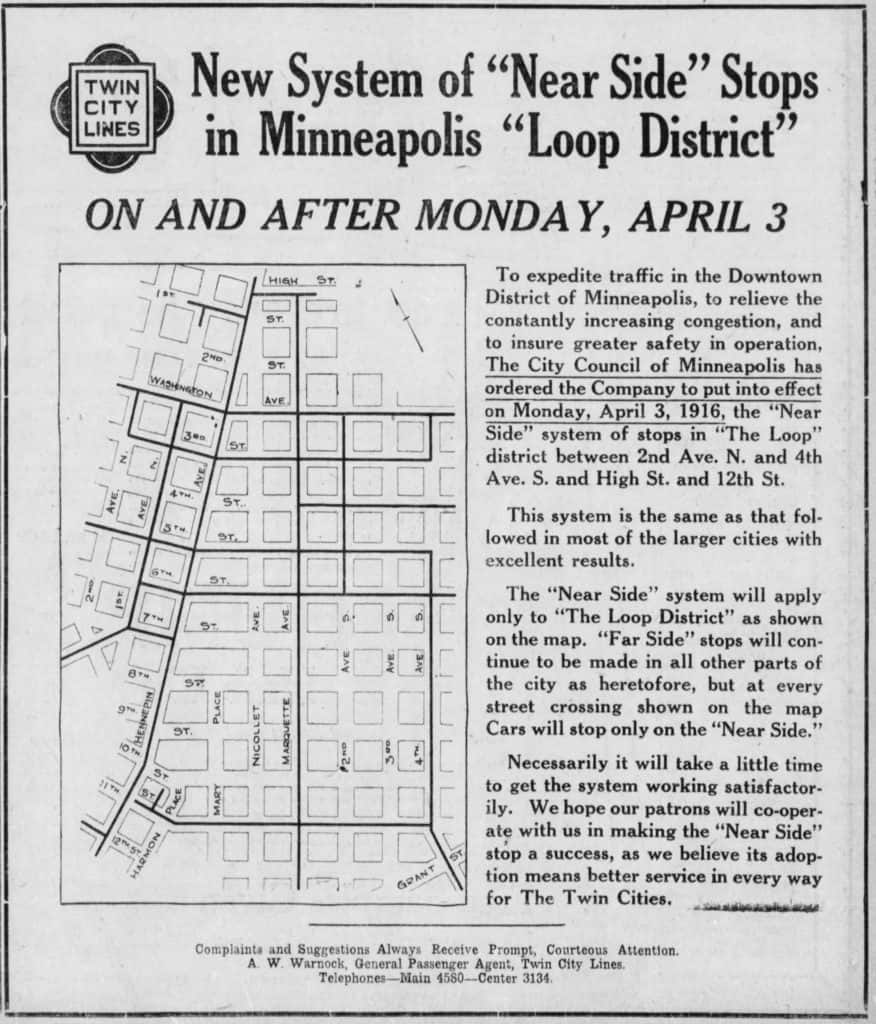

Since the commercial and warehouse sections of downtown Minneapolis were known as “The Loop,” streetcars that made it to this part of town were servicing the north Loop.

1916 Minneapolis Morning Tribune

Throughout today’s North Loop, you can see intriguing design elements in these old warehouses, created by some of the leading architects of their day. The man who designed the Lindsay Brothers warehouse, Harry Wild Jones, was a nationally-known architect who also designed the Lakewood Cemetery chapel. The old Maytag facility was from architect Christopher Boehme, one of the men who designed what’s now the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis. And an old warehouse at the corner of 1st and 1st (now River Valley Church) got a major re-design by the same architect who did the U.S. Supreme Court building and the Minnesota State Capitol, Cass Gilbert.

“Owners wanted to create an image for the company and create a visual presence,” said Anderson. “With the John Deere Company, there were two terra cotta deer heads on either side of the entrance to help advertise this company. Or the Sherwin Williams Company had a globe above their entrance with paint spilling over their ‘Cover the Earth’ logo just to advertise who they were.”

But eventually, these companies would turn to newer forms of transportation that were more flexible and economical than freight trains. That meant they no longer had to be clustered so tightly in tall buildings along the railroad tracks.

Along with the Great Depression, that meant a steady decline for the North Loop. Many companies left for bigger spaces in outlying areas. The old warehouses and factories fell into disrepair as they sat along deserted tracks and the downtown business district expanded away from here.

But because this area attracted so little interest for decades, these old buildings weren’t being torn down to make way for new high-rises, like in other parts of the city.

“This district has slept quietly through these decades following the Great Depression and this area came into the modern era much as we see it today,” said Anderson.

Now, it’s part of the charm of today’s North Loop, the historic features that remain, in classic buildings modernized for the 21st century.

“Sometimes you can see the most amazing architectural details simply by looking up toward the top of the building,” said Anderson. “There are still buildings where you can see painted signage that reflect perhaps several owners over the course of the building.”

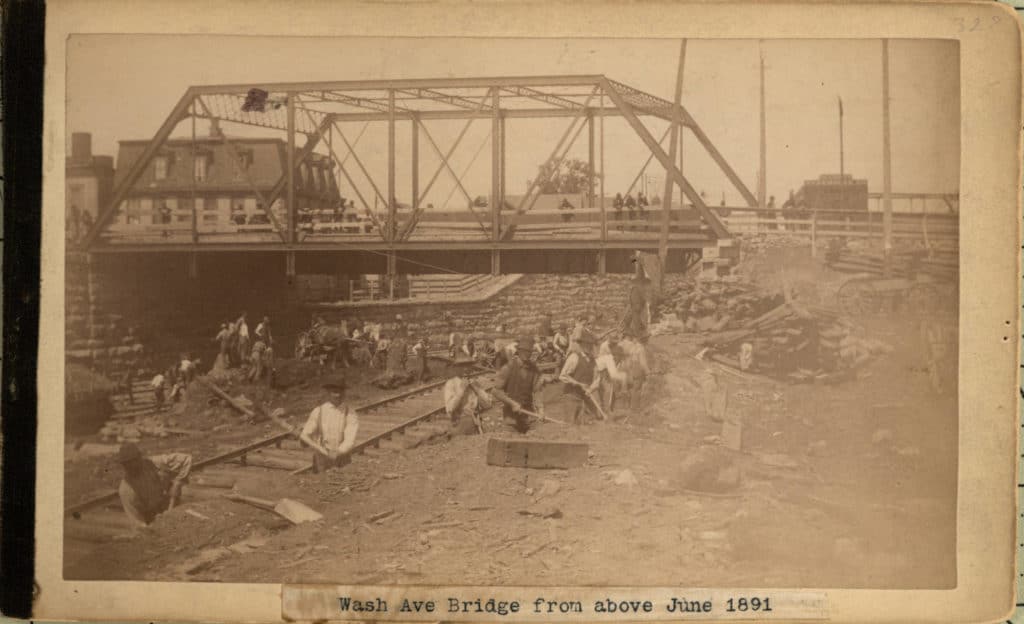

Photo courtesy: Hennepin County Library

“Some of the stone work that you still detect here in the district near the bridges or the rail yard, I mean these are massive stones, like Herculean in scale and that, I think, is really helpful for us to understand this district.”

It’s a district that helped spur Minneapolis to become one of America’s great cities. A district moving forward now, toward an even stronger future, with a healthy appreciation for the past.

Please visit the Historic North Loop section of this website for many more fun photos and articles about our neighborhood’s history.

By Mike Binkley, North Loop volunteer*

(*not an actual historian; I just pulled together information from newspaper archives, public records, online searches and most helpfully, the digital archives at the Hennepin County Library)

(Editor’s Note: The video identifies the BNSF bridge as being built in the 1880s. It actually went up in 1893. The metal truss dates back to 1963.)